MEMORIAL TO A COW

Across England there are headstones erected by farmers to memorialise the death of herds of their cows. James Bowen visited four of these memorials and reflects on what they tell us about the relationship between farmers and their livestock.

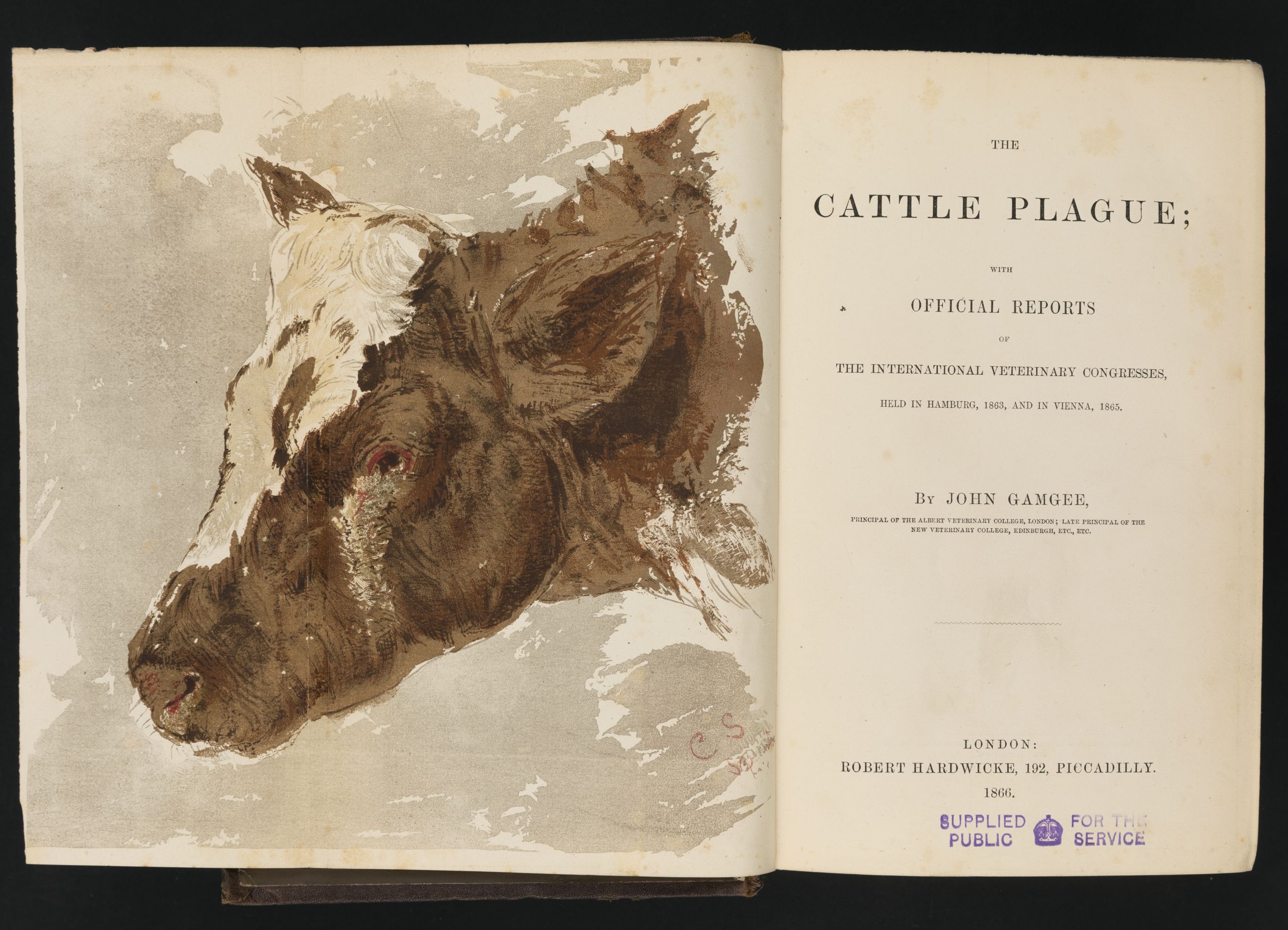

The Cattle Plague

Market Drayton is in north Shropshire and well known for dairying and livestock rearing. Between 1865–7, farms here and in neighbouring Cheshire and Staffordshire were devastated by an epidemic of cattle plague (also known as rinderpest or steppe murrain) which was so bad that it led the government to establish the State Veterinary Department.

On 7 August 1865 The Manchester Guardian quoted Professor John Gamgee (1831–1894), a notable British veterinarian who specialised in contagious diseases of cattle and horses:

"...From Market Drayton… we learn that on one farm 33 out of 35 heads of cattle have died, and there are reasonable grounds for fearing further losses in the same neighbourhood..."

The following week (14 August) it was reported by the same newspaper that the Market Drayton Agricultural Society had issued a circular describing the symptoms of the disease and the measures required to prevent its spread. The press reported that the main way the disease spread was by the trading of cattle between dairymen and farmers. Herds were not self-contained as many are today.

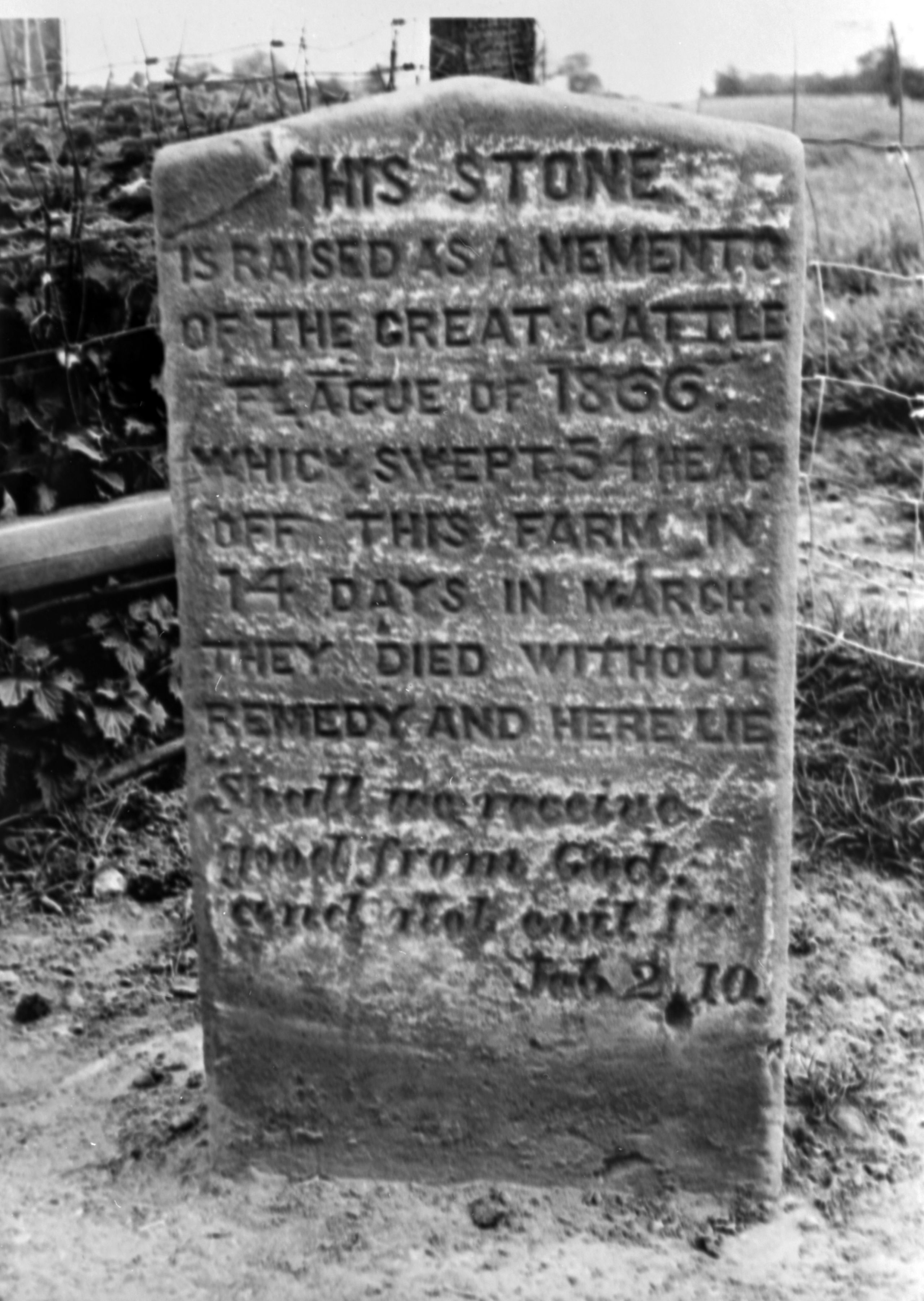

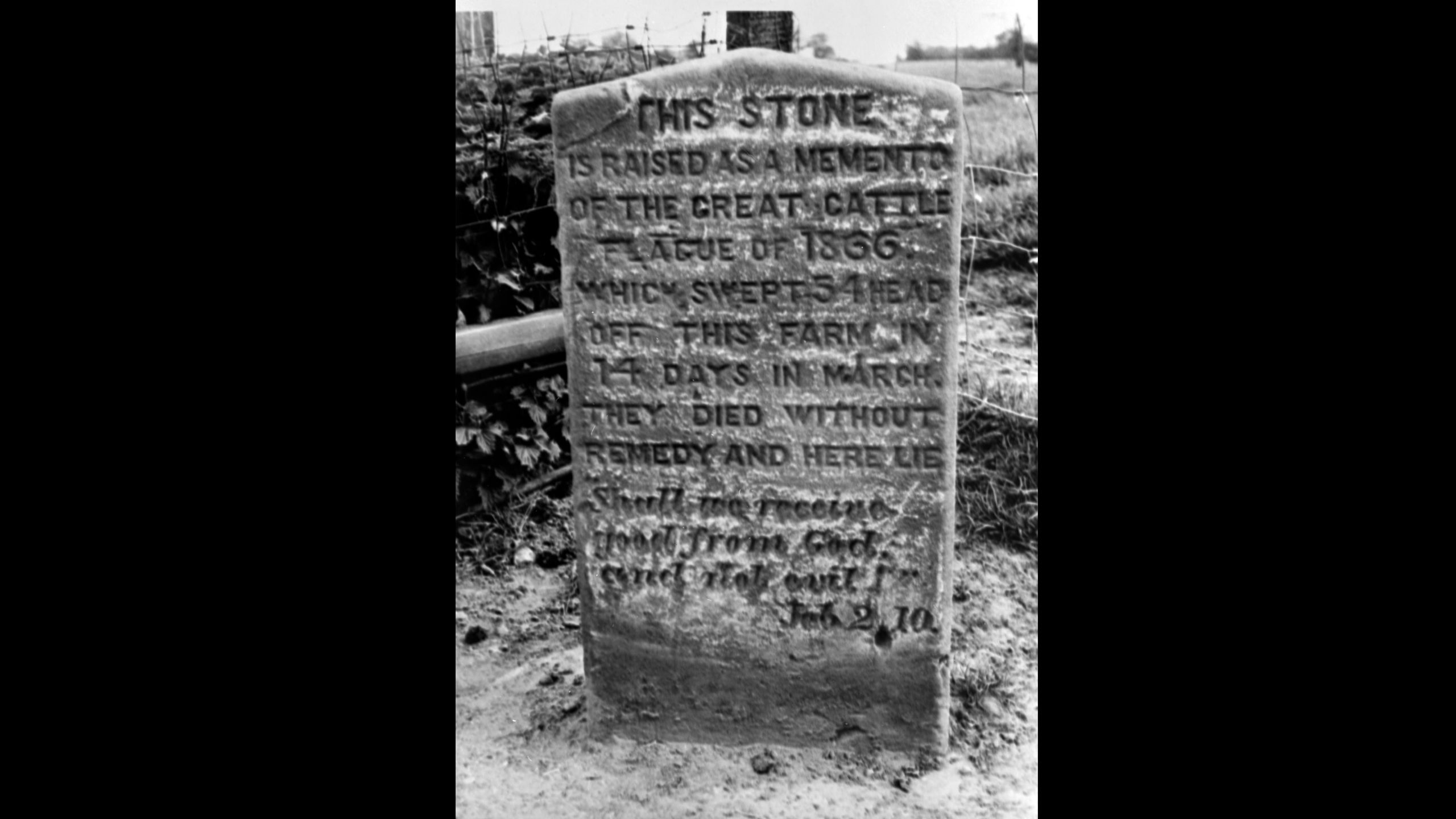

Norton Farm, Norton-in-Hales, Shropshire

This simple, sandstone memorial is known locally as the murrain stone. It measures approximately 40 (width) x 76 (height) x 30 (depth) cms, and sits to the south of the village, in the corner of a horse paddock near Norton Farm. The inscription, which is worn, reads:

"...This stone is raised as a memento of the great cattle plague of 1866 which swept 54 head off this farm in 14 days in March. They died without remedy and here lie..."

Earlier photographs show that this is followed by a Biblical verse: ‘Shall we receive good from God and not evil. Job 2. 10.’ It is the only memorial located with a religious reference.

Rectory Farm, Mucklestone, Staffordshire

This is an elaborate memorial, resembling a Victorian style gravestone, which is now in the garden having been moved to allow for the construction of new farm buildings. It measures approximately 30 (width) x 84 (height) x 18 (depth) cms. The inscription reads:

"...In this ground are buried forty head of cattle which died of murrain in the months of December 1865 and January 1866, the property of Richard Bourne, Mucklestone..."

Bourne was a tenant of the Right Honourable Hungerford Lord Crewe, but the farm was later bought by his family who still own it.

Lower Farm, Bearstone, Staffordshire

This memorial in the farmhouse garden measures approximately 45 (width) x 107 (height) x 14 (depth) cms. It was originally at Bearstone Grange but has been moved on several occasions. Again, this is much larger than the memorial at Norton-in-Hales and, like the one at Rectory Farm, is more akin to a gravestone. The inscription reads:

"...This stone erected as a memento of the great cattle plague. 62 head were swept off this farm during the winter of 1865 & 66 and are here buried. The property of Daniel Eardley of Bearstone, tenant to Mrs Kinnersly...."

The current owner of the farm, who keeps a large dairy herd, said that Daniel Eardley named on the memorial was his great-great-grandfather.

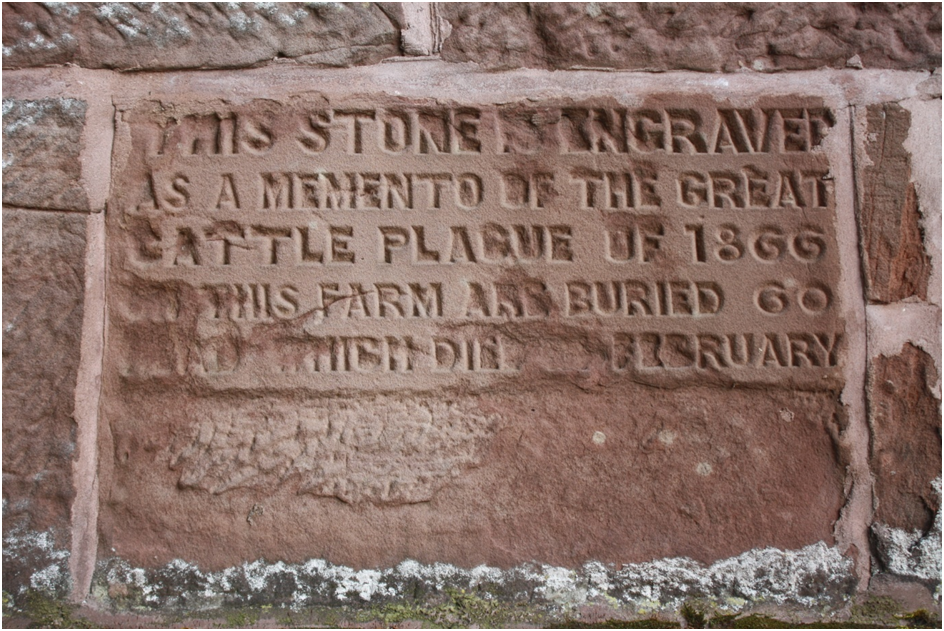

Willoughbridge Lodge, Mucklestone parish, Staffordshire

The memorial at this farmhouse (a former hunting lodge) takes the form of an engraved stone built into the exterior of a gabled wing. It measures approximately 60 (width) x 42 (height) cms. The inscription reads:

"...This stone is engraved as a memento of the great cattle plague of 1866. On this farm are buried 60 head which died [the stone is worn] February...."

This was a comparatively large herd. Animals were slaughtered in order to reduce the spread of the plague.

A sense of loss

Clearly the decision of farmers to commemorate their livestock reflects not simply the scale of losses, but the close emotional and working relationship which farmers and the wider farming community had with their animals.

The memorials preserved the memory of the animals and the dramatic impact the cattle plague had on the farms affected. The numbers given on the inscriptions suggest that all the animals in the herds mentioned would have been lost.

A special rate was levied to compensate farmers for losses. Memorials are more likely to have been erected by the larger farmers. Shropshire Archives holds numerous assessment books, as well as detailed accounts of the cattle plague at particular farms.

Just as today when animals and whole herds have to be slaughtered due to Bovine Tuberculosis or Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) outbreaks, farmers must have suffered stress and a profound sense of loss.

Although the last incidence of rinderpest in Britain was in 1877 and it was eradicated worldwide in 2011, farmers still appreciate the significance of these memorials, particularly if they recall contemporary outbreaks of FMD.

These stones illustrate the historically close relationship between farmers and their livestock.

James Bowen is a research associate at Leeds Trinity University who has published work on the history of animal welfare.

Archive images © Museum of English Rural life

Black and White photograph of gravestone, Shropshire, 1965. MERL 35/14071

1865 newspaper cuttings. MERL DX1276

1866 Cattle Plague Report. MERL 4340

All other content © James Bowen