ONE HISTORY OF A KNACKER

Writer and farmer Tony Harman (1912-1999) tells the story of Harry Wing, a local knacker who helped farmers in 1920s Buckinghamshire.

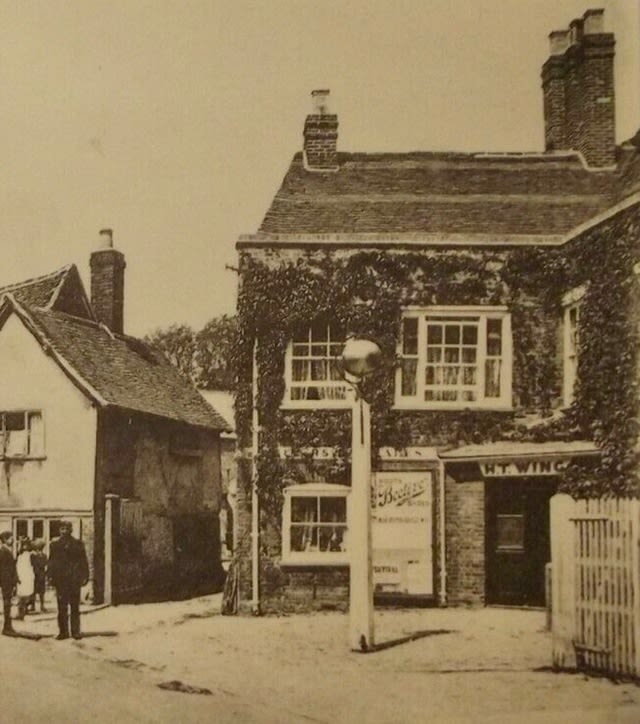

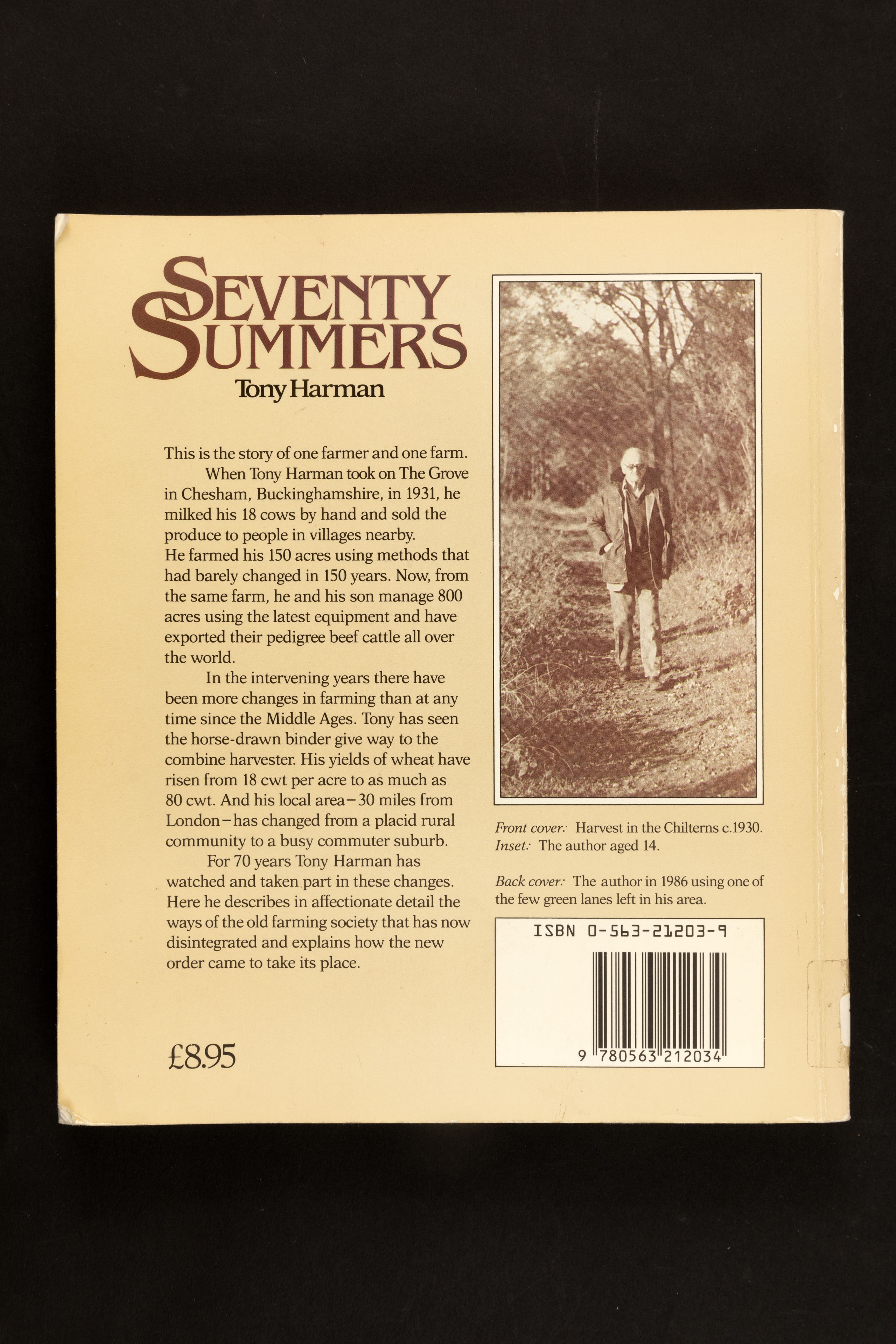

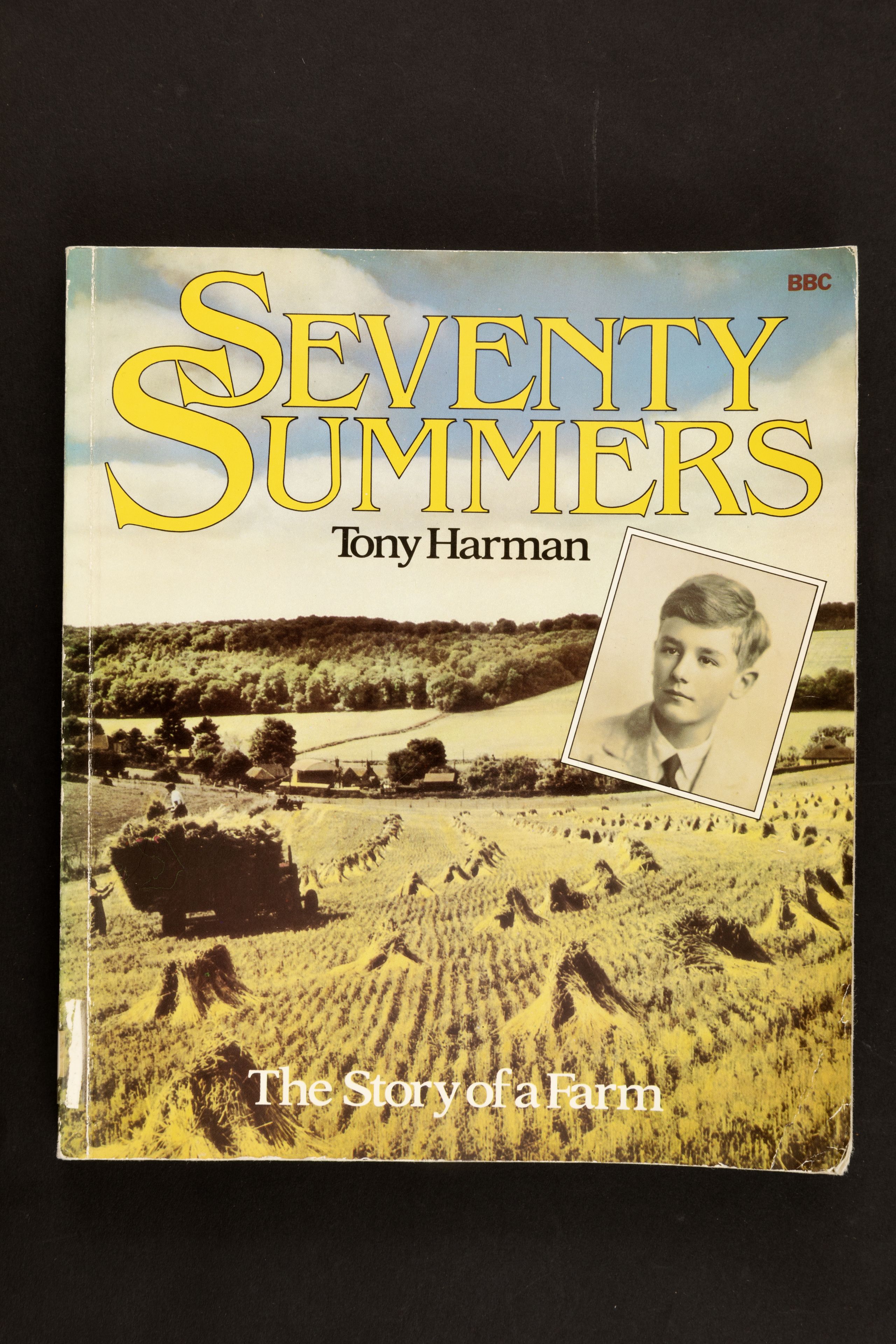

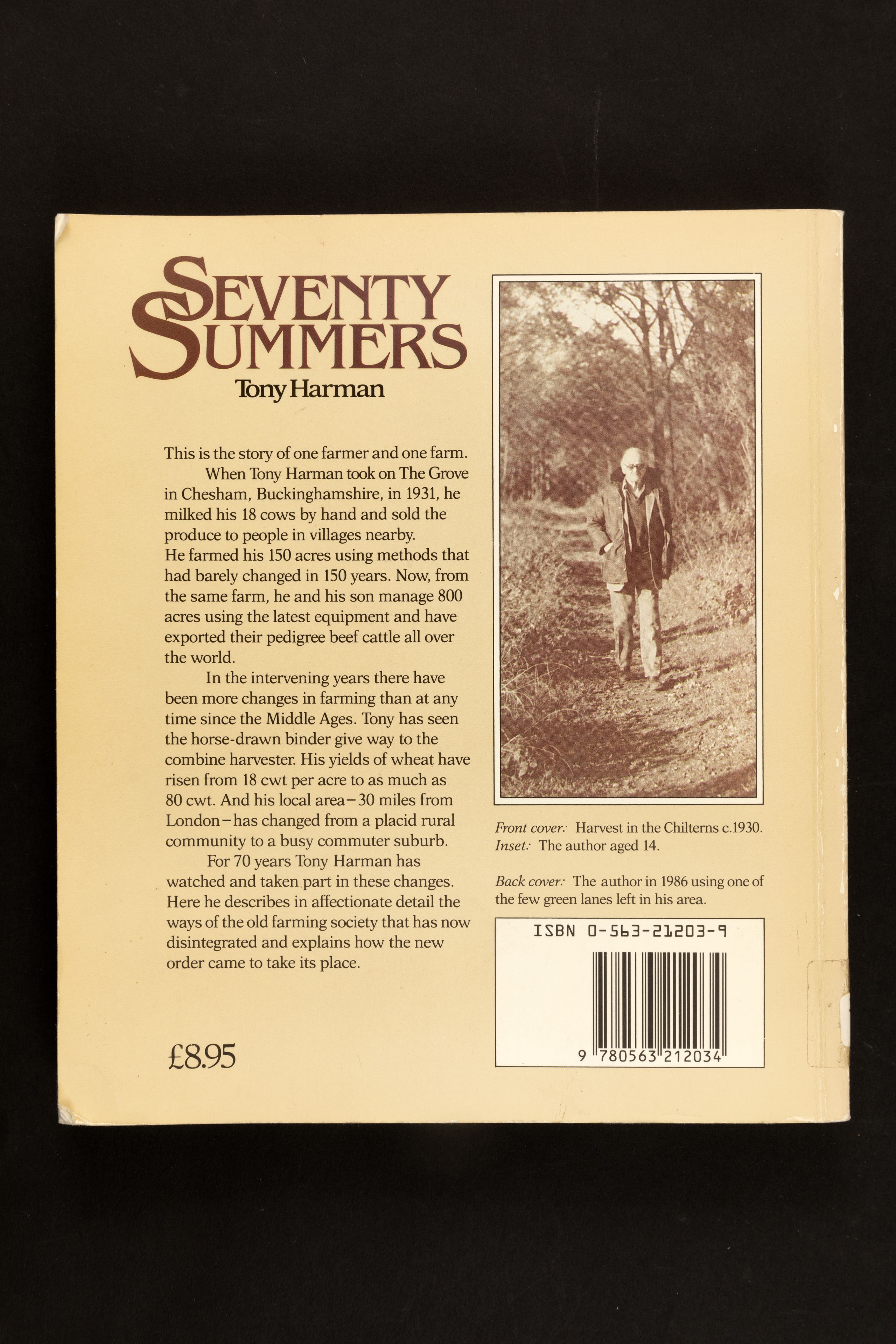

Tony Harman (1912-1999) was a writer and farmer, and the author of Seventy Summers (1986), a best-selling book and BBC television series. He was considered progressive in his farming methods. In Seventy Summers he described in detail his sick and injured farm animals and how they were tended to. Here he describes the role of the local knacker in 1920s Buckinghamshire.

New Skills

With the increase in dairy cattle during the twenties, new skills became necessary and the influence of vets became more important on the farm. Captain Wilson, the stone-deaf vet from Berkhamsted retired and was replaced by a younger man. But far more important than the vets was the local knacker.

I suppose there was a knacker in every district - somebody who was prepared to come and remove dead animals at short notice and dispose of them. Since the livestock was very unhealthy, there was a lot of this sort of work to do. Tuberculosis was rife amongst cattle and frequently spread from them to human beings. Johne’s disease, brucellosis, you name it, all of them occurred very frequently and they were all things about which the vet could do absolutely nothing and against which the patent medicines too were completely ineffective.

Harry Wing

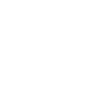

The local knacker in Chesham was Harry Wing, and he would come, in the early days with a horse and cart, later on with a lorry, at only an hour or two’s notice and remove dead bodies or put down animals which were too sick to recover. Originally, his trade had mostly been in horses.

He kept the Golden Ball public house in Church Street, Chesham, and behind it had some sheds and stables where he carried on his trade. Such a gory business would not be allowed in the middle of the town these days and certainly would not be acceptable immediately behind a pub. Somehow or other, he managed to keep it fairly clean and tidy and he had some farmland of his own where he would dispose of some of the waste products. In Church Street, he would sell some of the more healthy parts of the animals to local dog and cat owners, and occasionally people would buy it to cook up for their pigs or poultry. In those days, there were no patent tinned foods; no doubt those that exist now are made of about the same thing that Mr Wing used to sell.

Harry Wing’s pub, The Golden Ball, Chesham

Harry Wing’s pub, The Golden Ball, Chesham

Mr Wing seemed to conduct his business on the lines of a charity, which he completely controlled himself. What he paid you for the animals he collected would vary considerably from visit to visit. The factors he took into account were how easy the animal was to collect, how much meat it had on it and how much sympathy he had for you. If you had a lot of losses, it was very noticeable that the amount he paid you for carcasses gradually went up.

Because he had dealt with thousands of sick animals, he knew a lot about the job. He would do autopsies on your animal and report to you what had been wrong with them which, just occasionally, gave you some lead as to how to avoid further trouble. Also, if he came up to see an animal and he did not think it was necessary to slaughter it, he would tell you so and maybe suggest some form of treatment, in particular with regard to horses about which he was a real expert. He gained a tremendous reputation among the farming community and they had great faith in him. On occasion, this faith was taken to somewhat bizarre limits.

He told me himself of an occasion when, one Sunday afternoon, after the pub had closed and he and Mrs Wing were sitting quietly in their parlour dozing, there was a tremendous clatter up Chesham High Street and he heard a horse and cart turning into his yard, rattling on the cobbles. He looked out of the window and recognised a farmer from some six miles away, driving what he knew to be a very young and quite frisky horse, who was in the most terrible sweat, having been driven very fast. There in the back of the pony cart was something else, wrapped up in rugs. The young farmer jumped out of the cart and came running into the parlour saying, ‘Mr Wing, you’ve got to help me - my wife’s going to have a baby!’ She had gone into premature labour and instead of calling the local doctor, her husband had panicked and had come five or six miles to see the one person he had faith in- Wing, the knacker.

To this day, the knacker performs a marvellous service to farmers, though now, of course, there are fewer deaths among our animals. We know more about mineral deficiencies. The vets are better-trained. We have eliminated TB and brucellosis. We have nearly eliminated Johne’s disease. But still they die for one reason or another and still, anywhere in the country, there is a knacker who will come out any day of the week to remove the animal and dispose of it. Still, I believe, they give you, not necessarily what the animal is worth, but what their sympathy for you dictates.

Excerpt from Seventy Summers: The Story of a Farm, Tony Harman, 1986.

All content © BBC Books