THE SHEEP THAT DISAPPEARED

(THEN CAME BACK)

Nicole Gosling writes about the eventful history of the Merino sheep, how it originally came to Britain, disappeared and then came back again.

The Merino is a popular breed of sheep across the world. They are well known for their fine wool.

The wool is highly coveted by fashion producers looking to make comfortable, insulating clothing of the best quality. Despite this, there are almost no Merinos in the UK today, with the British sheep industry focused instead on meat production.

The roots of the Merino can be traced back to North Africa but it was first established in the middle ages in arid mountainous areas of Spain. For hundreds of years it was a highly protected breed. The Spanish monarchy wanted to keep a monopoly on it’s fine wool and it was a crime, punishable by death, to export the Merino to other countries. This monopoly started to break down in the 18th century; a combination of war, political turmoil and smuggling led to the breed slowly spreading across Europe.

Britain, like many other countries, was interested in having the Merino on home soil, as it promised the opportunity of improving the domestic fine wool industry. King George III was himself keenly interested in the breed as an avid agriculturalist and livestock breeder, and from the 1780s he employed a small team to smuggle Merinos into England. After more than a decade of small-scale importing, the King amassed enough sheep to begin selling them. From 1804, the Merinos were sold and traded across Britain in the hopes of establishing a self-sufficient fine wool industry.

However, the vision of Britain establishing a thriving Merino wool industry was never realised. By the 1820s there were other areas for sourcing Merino wool outside of Spain, which made the project somewhat redundant. For several years Germany was the prime supplier of Merino wool to Britain, however they were quickly replaced by Australia. Almost from the first days of colonisation, Australia had been producing fine wool destined for the British market—this wool could be produced more cheaply than in Britain because of convict labour and large areas of land, and because Australia was a colony, it was the next best thing to producing the wool domestically. Additionally, British sheep farmers were increasingly turning towards early-fattening breeds whose meat could be sold to the booming urban populations.

A significant hurdle to the plan, however, was that the Spanish Merinos did not thrive in the British environment. These animals had been bred on the dry arid mountains of Spain, and they seemed to struggle on the lush wet pasture of Britain, being described as ‘sickly’ and suffering dramatically from diseases such as liver fluke and in particular, footrot. Those who kept Merinos found that they required more attention because of their poor health, and as such were not easy to manage, nor profitable to keep. At the time, the poor health of the Merinos was understood to be a result of imbalance between the animals and the British pasture; essentially, they were sick because they didn’t belong in the UK. After a short time, most breeders abandoned the idea of keeping Merinos, and instead, the sheep were sent to Australia to become part of the growing wool industry there.

Over the ensuing years, there have been several attempts to re-establish Merinos in the UK, but all failed, and Merinos have ultimately gained the reputation as being inappropriate animals for British pasture, and more likely to suffer from diseases like footrot.

One farmer in Devon is disproving that theory, and over the past fifteen years has made a success of reintroducing Merinos from Australia into the UK. Lesley Prior knows much about the breed’s history in the UK and Europe and, just as importantly, the changes and developments in the animals since they were exported to Australia 200 years ago. We talked about Merinos historic reputation and how they can work on a British farm. During our conversation it quickly became clear that talking about ‘Merinos’ is no longer appropriate in 2021. What was once one breed has now exploded into a number of recognizable strains. Lesley explained that this was a result of Australian breeding which:

“Over 200 years, [diversified] the basic Merino animal into multiple different phenotypes to fit different climatic conditions, different requirements either for carcass, or for more volume of wool, or for an animal that could cope in severe drought conditions. So you know, a massive diversity within the one breed.”

So, when we talk about Merinos today, we are talking about a group of sheep with different phenotypes suited to different contexts. Over time, Australian sheep farmers expanded across the landscape, and came across a variety of environmental conditions, including those similar to the UK, and because they were motivated by a booming wool industry unlike their British contemporaries, they committed to breeding animals which could survive in those conditions. So today, there are types of Merinos that can thrive on British soils because they were bred for similar environmental contexts—unlike the ‘Merinos of yore’ which came straight from the mountains of Spain.

The diversity of Australian Merino breeds today in contrast to the Merinos imported from Spain in the eighteenth century explains both why previous attempts at establishing the breed failed, and why Lesley has found success today. I asked Lesley about the reputation of Merinos as being ill-suited to the British climate, and particularly their propensity for footrot. Lesley told me that footrot was just one of the problems that could arise from keeping sheep in the

wrong place:

“The experience in the UK would indicate that people who’ve had them here in the past have had high levels of foot rot. But when you think that the poor beasts have been totally unsuitable for the climate in the first place, because they were the wrong phenotype—that was just one of 100 things that went wrong with them.”

From my conversation with Lesley it became clear that keeping sheep in the wrong place can lead to a host of problems for the animal and the farmer. The animal may suffer from disease, or struggle to grow, while the farmer will need to work harder to keep the animals alive, and to produce good wool.

To keep Merinos in the UK today, it comes down to selecting the right type, which means from areas of Australia with a similar climate to the UK. According to Lesley, ‘that’s why [her operation] works’. So, in contrast to the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the British sheep farmer today has a much wider selection of animals available – and can therefore make choices that will allow Merinos to thrive in the UK.

Nicole Gosling is a researcher at University of Lincoln the focus of her work concerns the history of lameness in sheep.

Merino sheep photographs © Lesley Prior

Merino Ram etching from Sheep breeds and management, John Wrightson, 1893

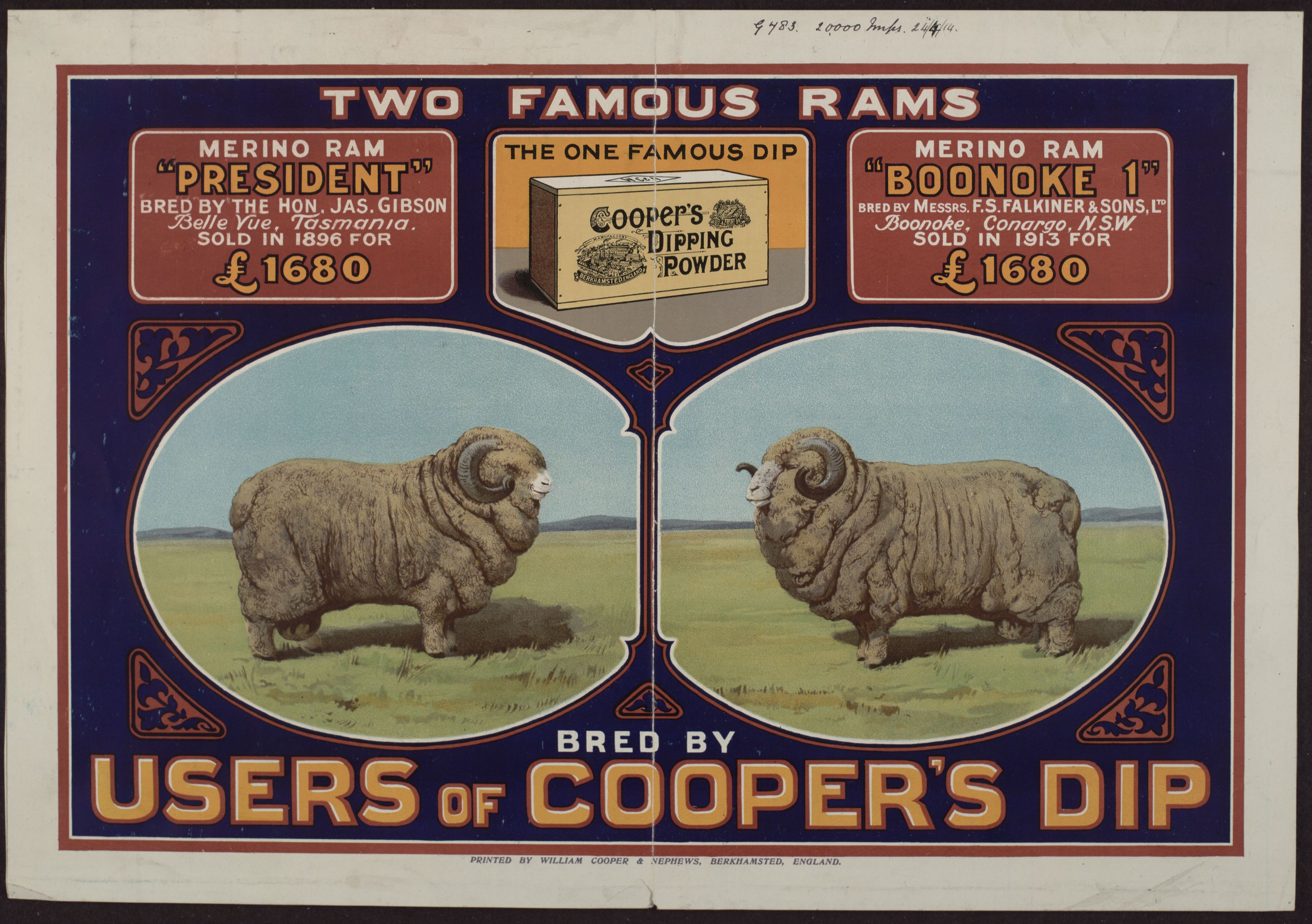

Cooper’s Dipping Powder Advert, 1914 MERL TR CMR P3/A2 © Museum of English Rural Life