WHY DID THEY PAINT FAT COWS?

Jacqui Winston-Silk from the Museum of English Rural Life tells us why animals like cows and sheep in the 18th Century looked so fat.

they were to be figured monstrously fat

Livestock portraits of prize animals like cattle, oxen, pigs and sheep became popular in the mid-eighteenth century.

These commissioned portraits are important because they record how English livestock farming methods started to change; they show a shift from medieval to more modern methods of breeding livestock.

Cows, sheep and pigs increased in size during this period for one reason: the production of meat to cater for the ‘the growing demands of the urban tables of Britain.’ 1

And it wasn’t just meat that people were interested in consuming. More people wanted to own art.

New developments in printmaking like mezzotints, aquatints and lithographs made buying and owning artwork more accessible and affordable. Images could also reach a wider audience through widely distributed printed publications and periodicals.

Farmers developed new ways of enlarging their animals. They shortened the period between birth and maturity for meat-producing animals like sheep and cattle. Flesh was redistributed to the most edible parts of the body.

The most desirable qualities were achieved through inbreeding, linebreeding and importing new cattle from overseas to be aggressively bred.

MERL 53/382

MERL 53/382

Livestock Portraiture

Paintings of livestock followed a tradition of sports painting. Sporting pictures reflected a growing passion for field sports and country life. Under the patronage of so-called gentlemen, paintings depicting scenes of hunts and races, with portraits of greyhounds and horses became very popular.

Agricultural enthusiasts followed suit and commissioned painters to record their favourite prize winning animals. Paintings were made at the expense of gentleman breeders for whom pedigree breeding was a fashionable hobby.

But were the animals actually this fat?

In a word, no. The portraits, most often of a specific animal, were executed in side view and often included the individual animal’s name, pedigree and physical description. Over-fed animals were represented because of their high meat or milk yields.

Artists were encouraged to over-emphasise the effects of improved breeding. In a 1964 catalogue of the livestock painting collection held at MERL, the author notes that the commissioner ‘paid for exactly what he held in his eye as the most desirable features… they were to be figured monstrously fat before the owners of them could be

pleased.’ 2

MERL 64/44

MERL 64/44

The Rise of The Livestock Portrait Painter

In 1763 a law passed in 1763 that limited the number of shop-signs on London streets. This resulted in a high number of sign painters turning to livestock portraiture. For many, this earned them a handsome living.

This is a portrait, painted by Thomas Weaver of Shrewsbury in 1831.

William Henry Davis was one of the most prolific artists of this kind of portraiture. Already a reputable sporting painter, Davis responded to the demand for livestock portraits by utilising lithography and publishing within his practice. Farmers’ Magazine, the agricultural journal, commissioned Davis to record winning animals at agricultural shows. He reproduced over 160 livestock paintings in almost 30 years for Farmers’ Magazine.

MERL 64/96

MERL 64/96

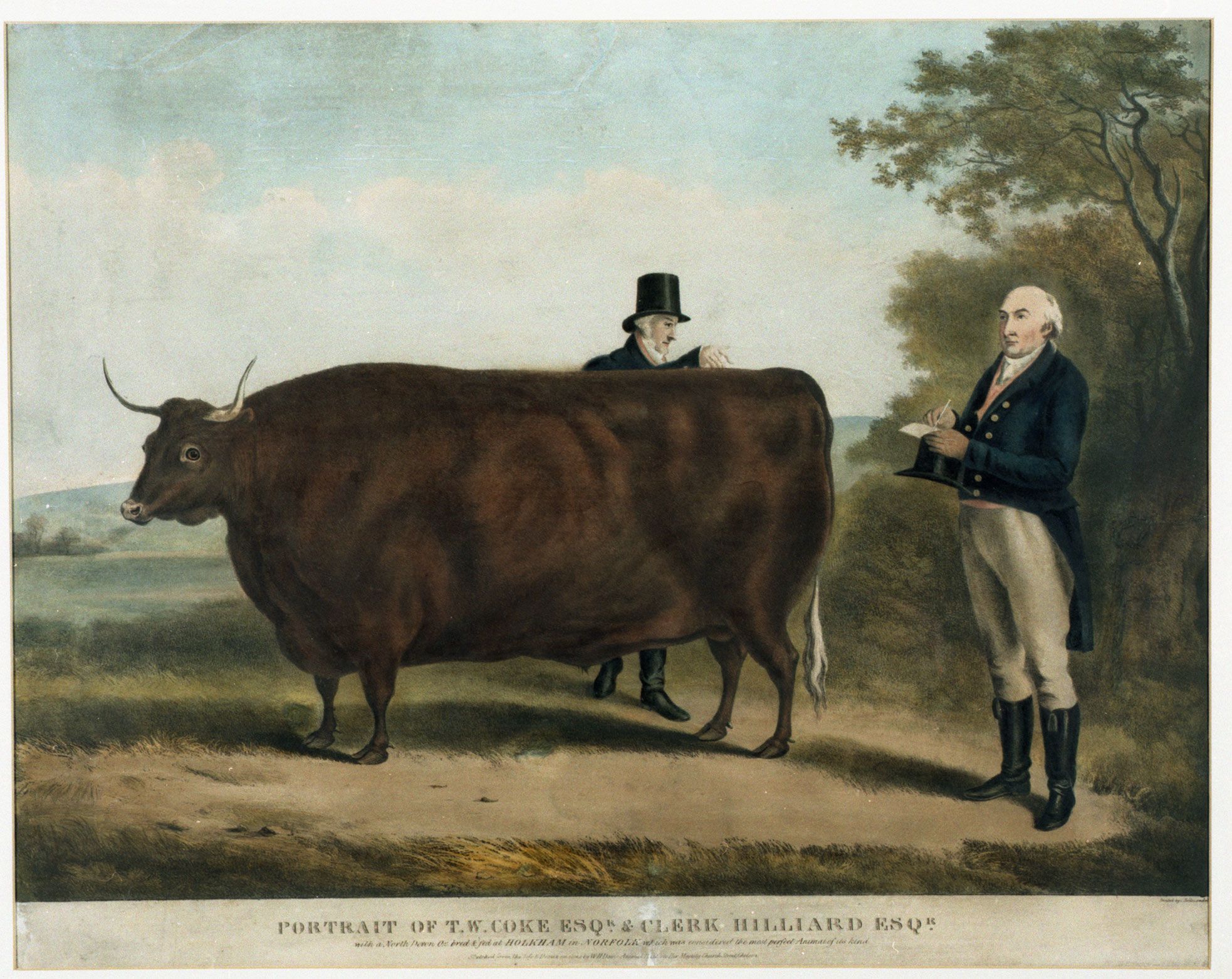

This is a print from a lithograph of a painting, entitled ‘Portrait of T. W. Coke and North Devon Ox’, c.1837. The ox was bred at Holkham in Norfolk and was considered to be the perfect specimen. Short-horn cattle feature a lot in Davis’ work, but he also painted sheep and pigs.

Davis’ prints declared he was ‘animal painter to Her Majesty’; however this was a self-styled title.

Livestock Fame and Fortune

With the establishment of agricultural societies, innovations in breeding were increasingly published in journals like Farmers’ Magazine. Publishing images of livestock portraiture was an ideal way of disseminating new practices to farmers, many of whom were illiterate.

As agricultural societies spread and as methods of transport improved, animal shows were organised. This was an opportunity to bring together, in fierce competition, breeders and their stock. Prizes meant enhanced reputations. The subsequent demand for livestock portraiture to capture these decorated animals was high. The most gigantic beasts went on tour around the country generating huge profits for their owners.

Prints were sold as tickets or as souvenirs of the spectacle. The paintings and prints functioned both as advertisements for animals available to stud, but also to ‘reinforce their owner’s amour propre.’ 3

MERL 64/40

MERL 64/40

This is a painting of ‘The Champion Shorthorn’, showing the shorthorn cow, a man and dog, with a landscape background. It was painted and signed by William Smith of Chichester in 1856. The Champion Shorthorn won 1st prize at the Chichester Cattle Show in 1856.

The consumption of livestock prints flourished. Producing prints to be hung on walls was an entirely new venture which emerged at the end of the eighteenth century.

MERL 60/5855

MERL 60/5855

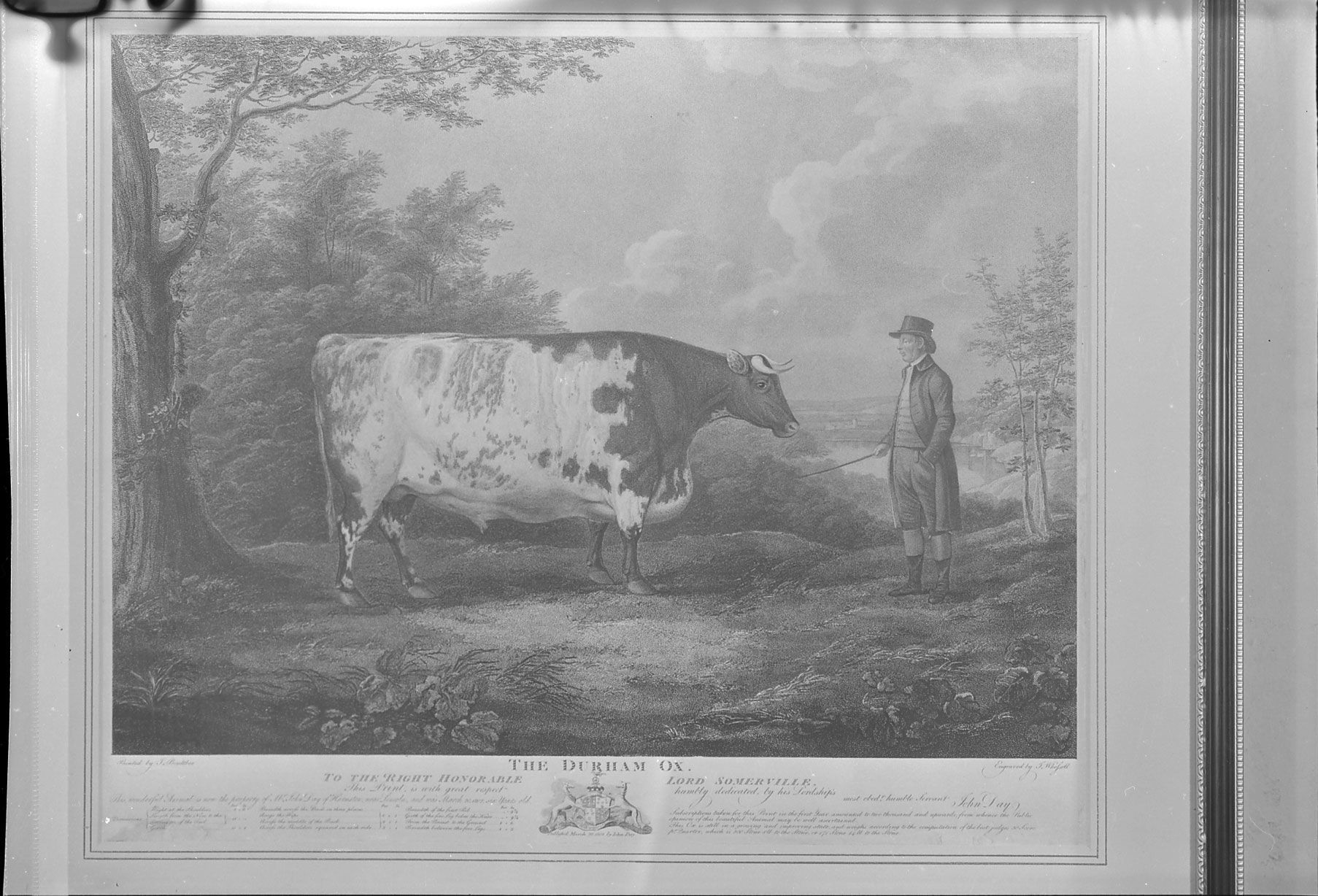

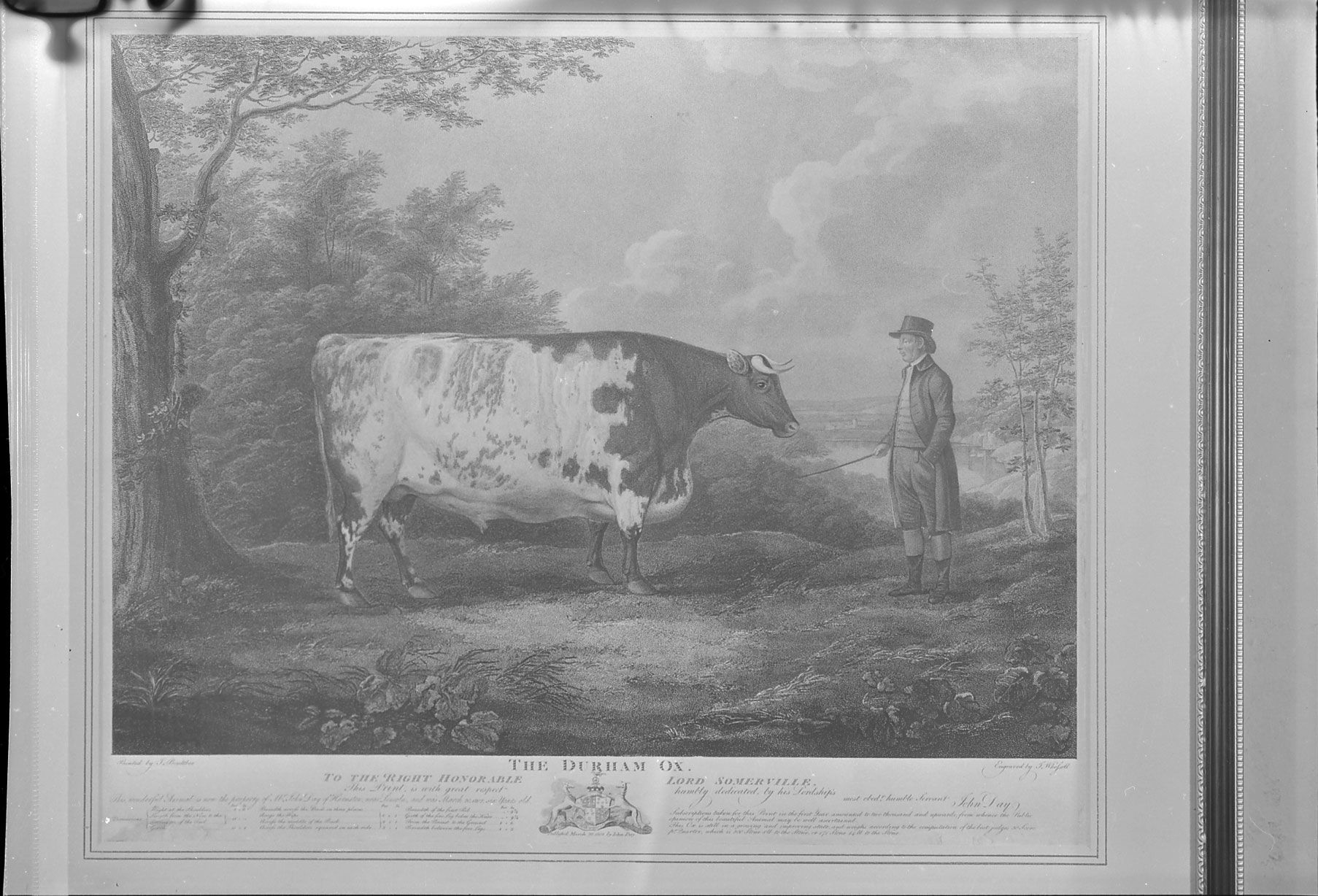

This is a print from an engraving of an original painting, ‘The Durham Ox’, by J. Boultbee in 1802. It was engraved by J. Whessell of Oxford and was published by John Day in 1802. Over 2000 copies of this print were sold within the year.

To satisfy commercial requirements, many prints were coloured by hand to replicate the original artworks.

Operating in a time before photography, the artworks also became an important means of advertising. Manufacturers of animal food adopted the livestock portraiture aesthetic in their marketing to increase sales.

Footnotes

1. Trow-Smith, 1957

2. Jewell, 1964

3. Melly, 1982

Abridged from Consuming the Fat Cows

by Jacqui Winston-Silk, Museum of English

Rural Life.

The collection of livestock portraiture at MERL can be viewed by appointment, for more information email merl@reading.ac.uk